If, like me, you’re new to the world of web design, you may have heard the term “design debt” getting thrown around a lot. As I hope to show here, the term is not as abstract as it first seems, and provides a great tool for costing the benefits of redesign projects.

But first, what does “design debt” actually mean?

Design debt refers to the “debt” accrued by adding features to a product without considering the functionality of the product as a whole. Design debt, like financial debt, may provide immediate gains, but it will generate interest over time, and eventually have to be paid off via a redesign (aka the return of the design time that was skipped to begin with). This may seem slightly vague, so I thought I’d take two real world examples of design debt, illustrating both its pitfalls and its potential.

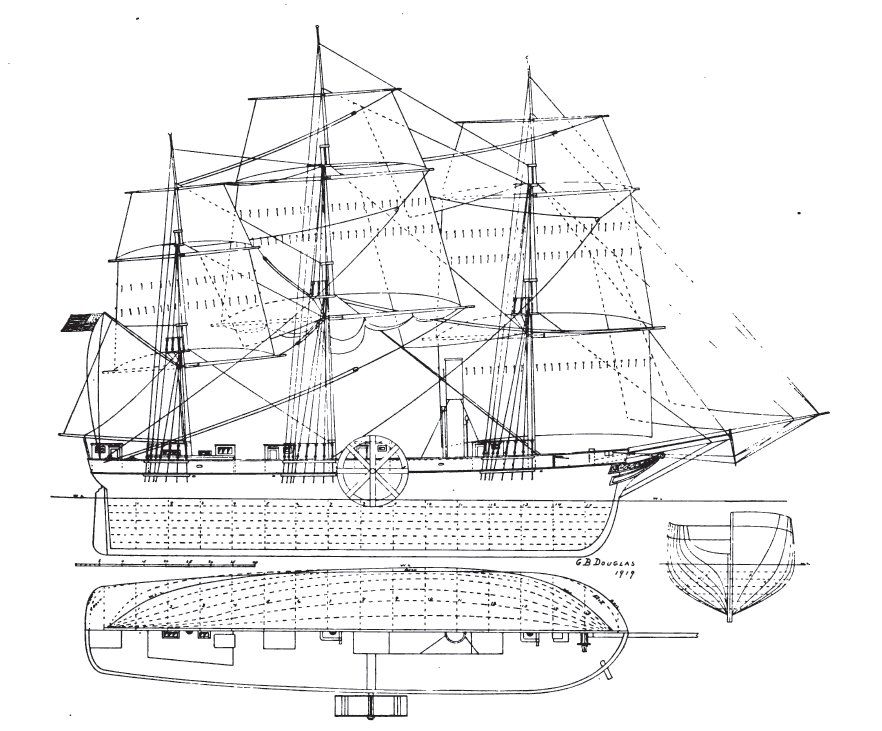

Design debt done wrong: The SS Savannah

The SS Savannah was built in 1818, and was the first steamship to cross the Atlantic. The Savannah was originally built as a sail ship, with a steam powered paddle only retro-fitted later. Whilst the design did function, it was ultimately less cost-efficient than existing sail ships. The operation of the paddle had not been considered when designing the rigging and hull, and this meant that the ship was not large enough to make full use of its steam power, and its sails made the paddle redundant for most of the journey. Meanwhile when the wind was less favourable, the large masts served to weigh down and slow the ship.

It was easier and cheaper to add steam paddles to the Savannah than to design and build an entirely new ship, but the returns on this investment were illusory. The ship was able to cross the Atlantic faster, but it did so with an inefficient and costly steam propulsion system, hindered by the design debt caused by its retroactive inclusion to the ship’s construction.

The SS Great Western, built twenty years later in 1838, was the first custom built steamship to cross the Atlantic under steam power. Whilst it also had rigging, its sails were intended to complement the paddles by keeping the ship on an even keel (and to propel it while the engine was under repair). The use of steam power was successfully incorporated into all of the ship’s design features, allowing it to function effectively and profitably throughout its lifespan.

Due to the fact that the Great Western was designed as a steam ship from the outset, the use of paddles provided a healthy return on investment. The ship did not suffer from the design debt of the Savannah, and its various components worked in synergy as a result. The ship’s hull, rigging and deck all facilitated and made the most of steam technology rather than hindering this novel form of propulsion. Rather than suffer from design debt, the Great Western benefitted from a forward-thinking design investment.

Design debt done right: Solar panels

A more positive example of design debt is also a more modern one: Solar panels. As of 2023, the world produces 1629 terawatt-hours of solar electricity per annum. Of this, rooftop solar panels account for 160 gigawatts of capacity, and over half of the annual growth in new capacity.

Rooftop solar panels are almost all retrofitted onto existing buildings, and these buildings were not designed to accommodate these panels. Nonetheless, the financial and environmental benefit from these installations is clearly significant and worthwhile. A major factor in this is cost, with the expense required to buy and install solar panels being a tiny fraction of the cost of the building that hosts them.

Of course, this is still a case of design debt. New buildings which are designed with solar panels in mind can find more efficient and aesthetically pleasing methods of incorporating solar power. This includes considerations such as roofing material (with metal roofs providing easier installation and longer lifespans), the incorporation of building integrated photovoltaics (BIPV), and even the angle of the roof (30° being ideal). Most importantly though, the design debt of adding a new feature to an old design (in this case solar panels to an existing building) is relatively small compared to the cost of building an entirely new structure. Here, design debt makes sense, and is worth undertaking.

Design debt as a concept: How you can use it

Design debt is a useful term even for those of us who do not (or cannot) design. At its most basic, it informs us as to the costs and risks of not engaging in design work. As I’ve shown above, sometimes this is worth it, sometimes it is not. Either way, it should be a frequent consideration on any project you work on. Most importantly, design debt reminds us to consider the opportunity cost of our actions, or lack thereof. Just because a system (or a website) works, it doesn’t mean that some design work cannot solve problems and provide significant returns.

As always, this is only a beginners guide. If you’d like to learn more from the experts, check out Nielsen Norman’s content on the subject, or better yet, get in touch with our expert UX team!